11. Soul

I’d like to take a break from our previous structure in which you have been reading a section and then explained it to your hound, possibly playing examples here and there. After awhile it could come off as a bit routine, so I like to try something different. In this chapter, I’d like to speak directly to your fur-covered learner over there, hopefully sitting next to you on your sofa, awake and ready for something new. All you have to do is read the following out loud to your friend, slowly and carefully, and deploying as many facial expressions as you can so that your body language will convery some of the concepts that might exceed your friend’s word vocabulary. Let’s give it a try! (I think the next sentence is a lock to get their attention.)

There’s been some discussion over the years about whether dogs have souls. There’s even been speculation whether, if there is, in fact, a heaven, you are likely to find your human there. It’s kind of a sad question, since if you enjoyed each other’s company in life on earth, you might think you’d be able to continue that friendship. Without them there, who’s going to throw that frisbee?

Think for a moment about the forever part of us, the part that feels like it’s somehow attached to what we see in the night sky, when we can lift our gaze from what’s close to us to what lies out there in the mysterious dark. For many of us, you probably better than me, can even divide these two worlds into what we can smell and that which we can’t. Or the immediate and the eternal. Almost the same thing.

When it comes to music, some human composers, like Bach, wrote almost all of their music for that realm that we can’t smell — even though it may often be performed in buildings where there’s lots of incense burning. But you can sense that this music is meant to rise up to the top of those immense buildings, and then waft beyond, into the night sky even when it’s day.

Other composers have attempted only a few times to write music that intends to touch the spiritual. When I was young and trying to figure out how to explore classical music, I happened to be at a concert that so riveted me that it suddenly gave my life a new dimension. For the first time I had heard the music of a composer that seemed to be trying to examine the nature of the soul’s mortality, and address his feelings about it in a mixture of wonder, of supplication, fear, anger, and eventually acceptance.

This was my first exposure to a type of music named Requiem Mass, and this one was by the great Italian opera composer who, if he had moved to the United States and Americanized his name would be known today as Joe Green. But he didn’t move, and so we know him in the much more sonorous way as Giuseppe Verdi. Verdi’s Requiem Mass has been criticized as too theatrical, too much in the spirit of opera. But Verdi wrote his operas about the great human dramas, and were full of profound spiritual insight into the human condition. The Requiem was Verdi’s authentic voice turned to the purely religious. He was so pleased with this Requiem that he took it upon himself to premiere it throughout Europe and England.

My first recording of Verdi’s Requiem was monophonic (before stereo) and there was the picture of an angel on each label of the two record set. The illustration showed the angel sitting on a record, and her quill was inscribing the groove of the record. The label, of course, was Angel Records, but the image and the music were so perfectly suited that I always associate that angel with inscribing Verdi’s Requiem. The conductor was Victor de Sabata, and the ensemble was the orchestra and chorus of what is one of the great opera companies in the world, La Scala in Milan. The records being twelve inches in diameter, meant the program notes were also twelve inches, so wider and taller than most books. I read the text along with the music dozens of times, reading in Latin with the English translation, trying to find any connection with my own heritage or with anything I was familiar with. The music spoke directly to my heart, but the text, with phrases such as “Deliver me, O Lord, from eternal death on that awful day,” distanced me from the music for many years. The music touched me, yet the text told me I was an outsider, looking in.

As a dog you might often experience that same feeling. There’s so much you love about being around humans but there’s also much incomprehensible stuff that goes on between them that it can be a little distancing. For me and this deeply felt religious music (religious but not my religion) I realized I had a choice — either I could take the music that spoke to me and accept it as being for me, too, or I could walk away from it, beautiful as it was, and put myself in the position of spiritual voyeur — I could notice it was authentically touching others but not allow it to touch me.

I chose to let the music in and let it speak to me, and use the text to help me understand how it might be intended for part of the audience. I would let it be mine to the extent I could.

You, as a canine, may find yourself making the same choice. Requiem masses are often beautiful because they are attempting to bring peace in a moment of sorrow and loss. But underneath their religious foundation, we might be able to see that they are about universal experiences of living souls, as we contemplate our connection to that which we cannot smell — the heavens.

If you find a requiem that touches you, look deeply into the eyes of your human friend and let them see that your soul has been touched (try not to pant, since that might convey the wrong message.) And then you might want to explore other requiems together. Some of the earliest are very close to Gregorian Chant, which we have thought about in an earlier chapter. The Spanish composer Tomás Luis de Victoria wrote two Requiems, the second of which, written in 1605, offers a beautiful sense of a purely chant-like requiem. I promise there will be times in the future which, after a particularly stressful day, you will both find solace with Victoria.

When I was a young subscriber to the Musical Heritage Society, they would send me all kinds of obscure records, some of which took me a long time (or never) to really get into. But one touched me more than others. It was an ancient requiem by someone whose last named started with Zw, but when the age of CDs came in and I shed most of my vinyl, a day came when I suddenly had a longing for that Zw whatever-his-name-was composer’s Requiem, but it had vanished. There were no composers with a name like that anywhere to be found. Had I dreamt this whole thing up?

Then after several years of this niggling at me, I had a brainstorm. Find the Musical Heritage catalog — surely someone had kept one — and find the Zw composer. And there it was: Polish composer Mateusz Zwierchowski and his Requiem of 1760. Now I could look for a CD or other modern recording. Mais, non! That vinyl LP was the only one, and it seemed to have escaped being remastered in CD form. What a tragedy — Zwierchowski had risen from obscurity, been recorded once, and then faded away. The only place I can suggest you find it is on YouTube, where it lives a fragile existence.

Other requiems you might want to include in this vertical are: Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, Mozart’s last Requiem (identified as K, or work number, 626) that forms the core of the ending of the film Amadeus, Brahms’s German Requiem, Gabriel Fauré’s Requiem from around 1890. And finally, you might want to spend some time with the exquisite, drop-dead gorgeous (maybe that’s an odd inducement to listen to a requiem) by Maurice Duruflé.

Duruflé was highly influenced by the Fauré Requiem, and the first time I heard the Duruflé Requiem I thought it was so heavily influenced that Duruflé needn’t have bothered writing his own. But over the years we have found that we rarely listen to Fauré’s Requiem, and it’s Duruflé’s that has offered solace on multitudes of evenings.

One wonders about a composer who wrote only a few dozen works and how he was somehow able to write a masterpiece, as Duruflé’s Requiem is. And the answer lies in knowing that Duruflé was often composing throughout his life, but mostly in the form of endless revisions. As an organist, he would work over his organ pieces for years, endlessly pursuing perfection.

I’ve probably heard the Duruflé Requiem too many times, and by now some of the mystery of it has become a little clearer. I’d like to go back to the first few times I heard it, and offer you my first impression of the first movement of the Requiem — called the Introit, which means entrance. The first sounds are murky. You can sort of hear an organ murmuring in a way that’s really hard to figure out, but it’s pretty busy in its own soft way, and the choir is singing something which they seem to know pretty well but they don’t seem too eager for us to share it all right away.

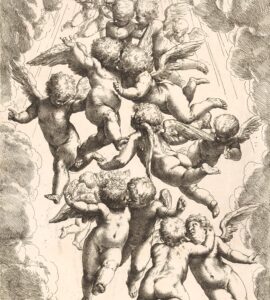

After the first movement is over, it just kind of fades away. What was that meant to be, that soft cloud of music doing? When I first got what was going on, it was kind of a shock: this is the fluttering of angel wings, hovering over us. Everything is soft, indistinct, and little-by-little, comforting. The entrance is bringing us into a spiritual place. We do not need to listen to the music — instead, the music is listening to us, to the sorrow in our souls, and comforting us.

There are three recordings you will want your friend to find for you, and sadly, two are not on Idagio. Easy to find Is Robert Shaw conducting the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Harder to find, but worth the effort, is Matthew Best with the English Chamber Orchestra and the Corydon Singers on Hyperion (they don’t lease their rights to Idagio.) This is the performance that seems to bring those hovering and murmuring angels very close indeed. And finally, there is an urtext performance captured late in his life, with the composer himself conducting a French orchestra and chorus. The recording is on the Apex label, now owned or distributed by Warner Classics.

Composers are often not the best performers of their own work (they hear too much in their own heads) but after you’ve gotten to know the Shaw and Best performances pretty well, you might find much of Duruflé’s own recording quite surprising.