9. A New World

In this section, I’m going to devote a few articles or chapters to favorite pieces of music that have kept my interest over the years. I hope some of these will delight you and the collared one. Who knows, your kids even might wander by as you’re listening and ask, ‘What’s that?” I know you’re laughing, but it could happen…

I have it from reliable sources that the notion of a dog’s year being equal to 7 human years is actually misleading. The first two years of a dog’s life are closer to 24 human years, so by the time your dog is hitting her third year she really ought to be in medical school if she has any brains at all. When you’re trying to explain to your dog what the end of one era is and the beginning of another, you’ll want to keep this in mind. Her sense of what constitutes an era might be shorter than yours.

Paris in the first few decades in the 20th century was a cauldron of revolution in the arts and even in human sensibility generally. There would be no going back from Picasso. Once Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald took up residence, the center of American literature moved there. And in music, classical met jazz, fell in love and had a few kids. You might try explaining to your dog how strange and magical it all was by mentioning if you had both been in Paris in the 20s and went to a dog park, you might have run into American dance sensation Josephine Baker walking her leopard, Chiquita. That would’ve sharpened your fight or flight instincts.

What a town!

Three composers shaped and emerged from the era. Igor Stravinsky had been recruited from Russia to come to Paris and write ballets for the impresario Diaghilev, and Stravinsky’s masterpieces were what Picasso was to art — he unleashed a new world. But Stravinsky was not yet ready to attempt to be influenced by jazz. In this period, he was thoroughly Russian and pagan.

The other two composers were the American, George Gershwin, and the Frenchman Darius Milhaud. Gershwin was a high-school dropout from the Bronx who managed to shape his own, fairly deep, education in classical music. But to make money, with his brother Ira as lyricist, Gershwin became one of the most prolific and brilliant songwriters of the jazz age, creating a non-stop string of musical hits for Broadway, quickly becoming rich and famous in his young twenties, maybe even the model for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Gatsby.

Milhaud’s family were almond growers and brokers, with deep roots in the Comtat Venaissin region in Provence, which had been a safe spot for French Jews since the 14th century. He may have developed some of his unusual musical sense by listening to the workers in the groves, as their various songs collided with each other, sometimes cancelling, sometimes reinforcing. Gershwin eventually found his way to Paris, but long before he actually got there, he was already hearing Paris through Milhaud’s music in concert halls in New York.

The bandleader Paul Whiteman shaped the country club sounds of the early jazz age. His music was clever, polished, non-threatening. But Whiteman was also adventurous, and decided to pull together a crossover concert of popular music and this new thing emerging from Harlem, jazz. He wanted an important piece to be the crowning moment of the concert, and after months of trying, he finally convinced 25 year old George Gershwin to write a concert-length piece that Gershwin could perform (Gershwin was a fabulous pianist) with the Whiteman ‘orchestra,’ which was really a large dance band.

Titled, “An Experiment in Modern Music,” all the notables of both popular and classical music were at the 1924 Manhattan concert, including Stravinsky, who had just been in Boston for the premiere of one of his ballets (and Gershwin had attended that!)

Most of the New York serious classical music critics hated Rhapsody in Blue on first hearing, but within a year it had been played in London on the radio, and soon was being performed around the world. It’s success encouraged Gershwin to continue to create a new kind of American music that fused Western traditions with uniquely American Black and folk music. His opera, Porgy and Bess, is a staple around the world, and, maybe not so amazingly, is the basis for a great many jazz masterpieces as well, including the album by Miles Davis.

I have always had my ear out for a recording that might evoke that legendary Paul Whiteman concert that introduced Rhapsody in Blue, but, alas, I do not believe there is one. A few years ago I thought I might have run into the mother lode when I was seated at dinner with Mitch Miller, famous for a lot of things in music including turning down the Beatles when he was an executive at Columbia records. It turns out that Gershwin’s psychiatrist had suggested it might be helpful for George’s mental health to personally introduce his classical music to the country. So Gershwin put together a 55 piece orchestra including 23 year-old Mitch Miller on oboe, hired two train cars and took a symphonic version of Rhapsody in Blue to the country. Mitch had carefully kept a complete score with Gershwin’s markups and notes throughout. And better yet, over dinner Mitch told me that he had just conducted a recording of Rhapsody with the pianist David Golub and the London Symphony Orchestra, which he promised to send me.

And unlike so many promises made after a couple of glasses of wine, the recording soon arrived.

I raced to put the CD on, full of anticipation. Here it was, the urtext!.

Milhaud conducts the urtext edition.

Unfortunately, Gershwin had apparently managed to wring the jazz energy completely out of this touring version in an attempt to please the broadest possible audience. The sense of improvisation is gone. Spontaneity is gone. What’s left just so pretty. I did not smash the CD into a million pieces. After all, it was a gift. But I thought about it.

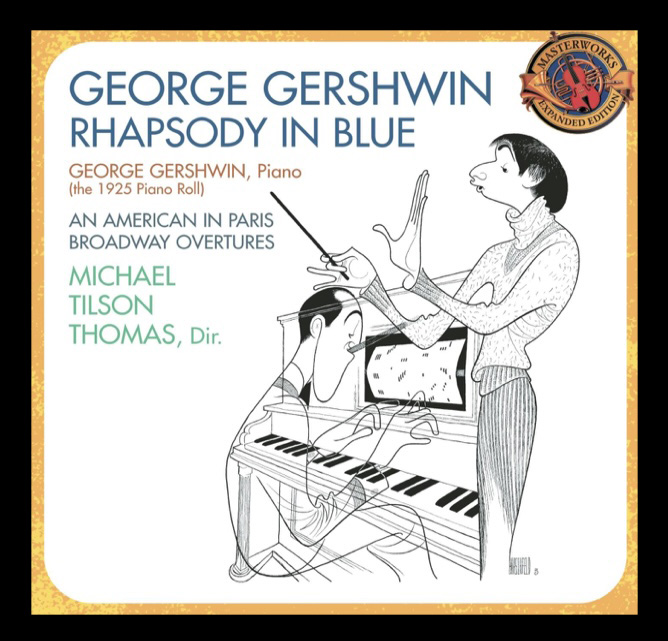

So what’s the best version, the closest to the original concert? Fortunately, Gershwin cut a piano roll for a very-close-to-the-original version of Rhapsody, arranged by Gershwin for two pianos. Isolate the parts that are the same as the original solo piano part, play it alongside a re-creation of the Whiteman Band with members of the SF Symphony with Michael Tilson Thomas conducting, and you’ve got something pretty wonderful. This is not one of your tinkly, crappy player piano rolls. This is Duo-Art, the Rolls-Royce of piano roll recording systems, and it captures that wild dynamics so well that its hard to imagine George is not actually right there, live, playing all over again. It’s that good.

Darius Milhaud already had a following in classical music by the time he encountered jazz. He was in London in 1920, heard his first live jazz, and needed more. He was soon in Harlem, absorbing the new music. Back in Paris, commissioned for a new ballet, he let his sense of jazz infuse his already well-developed voice.

The result, La Création du Monde, for me, is the great piece of music to come from Paris in the roaring 20s. It’s not a classical piece or a jazz piece — it is the actual creation of a new world, or a new sensibility. It’s free, it’s often chaotic, and it is infused with wonder and beauty. Written for a small ensemble, just as the original Rhapsody in Blue was, it was intended to be played from the orchestra pit, hidden away while the audience watched the ballet. On YouTube you can find various versions of the ballet, and to my taste, they’re all, how to be kind?, not worthy of your hound’s attention. These two pieces of music, so similar in sense and energy, were written only three months apart, one in New York, one in Paris.

What about Création recordings? Just recently we streamed Simon Rattle conducting it with members of the Berlin Philharmonic. Rattle is an extremely hip guy and highly sensitive to the early 20th century world, or so I thought. As the performance progressed, I began to realize that it was all so rounded off, sanded down and smoothed out so that eventually all the insanity of the piece had been Xanaxed out. I couldn’t stay to the end.

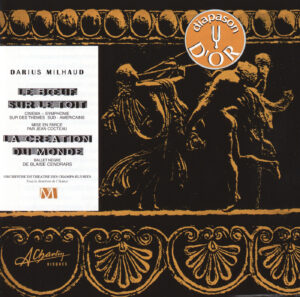

Unlike Rhapsody, there is a recording of La Création that tells us exactly what the composer had in mind. In the 1950s André Charlin put Milhaud together with the original ensemble that premiered La Création, and recorded it. When I first heard about it I began to search for this obscure recording, and finally found a copy. Just to refresh you on recording technique in the 1950s — there was no stereo. Most recordings from that era are ‘historical.’ You need to listen past the sonic limitations and get the best out of it that you can.

But not the Charlin recording. This recording is a miracle. The producer, Charlin, was actually one of the greatest inventors in the history of sound. He had introduced stereo into French cinema in 1934 for Abel Gance’s Napoleon. And this recording is in stereo — maybe one of the great, natural, stereo recordings of all time. So that’s the good news.

Why is there so often bad news to balance the good news? Is there some Jungian dark side to the human subconscious that always needs to balance everything out? Is this what your dog is sensing when he howls? So what’s the bad news? My favorite classical music streaming site, Idagio, which usually has the good stuff, does not yet stream this staggering recording. (This may change by late June, 2021, so check back on Idagio.) You’ll need to buy a copy if you like the piece. They’ll download you a flac file of it, and it’s just that good.

Update: Idagio now has Milhaud conducting Milhaud available.

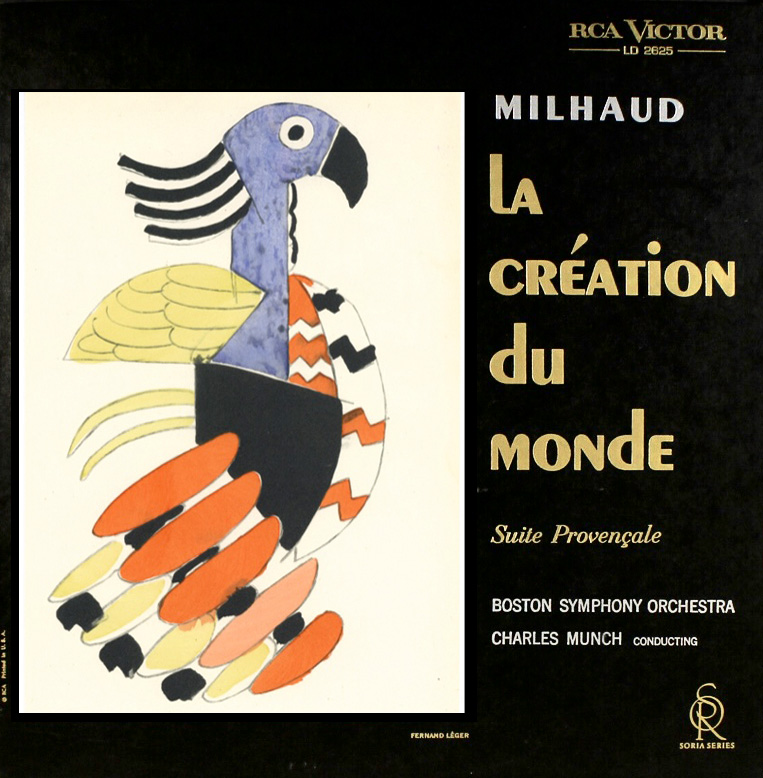

In the meantime, if you and the itchy one over there just can’t wait even a second longer for a little Milhaud, then let me suggest a couple of versions to hold you over. The conductor Charles Munch was in Paris in these glory days, conducted the premiere of several Stravinsky ballets, and later commissioned some of Milhaud’s symphonies. His version, with members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, is quite lively, a little colorful, a little jazz-infused. It’s a little like ordering room service from a three-star restaurant in a 12 story hotel, and the elevator is broken. It’ll get there, but the seasoning has lost something by floor five.

Another pretty good recording is by the excellent ensemble Orpheus in New York, famous for playing without a conductor, so they really have to listen to each other. Unfortunately, in an intentionally unruly piece like Création, they’re not really supposed to pay too much attention to each other all the time, so it’s a little too careful. Maybe someone should have brought a few bottles of Tequila to the recording session. Since they failed to, it might help if you make up for it at your end.

The greatest figure in 20th century music was not known for her compositions, although she did write. Nadia Boulanger, born in Paris in 1887, was teacher and inspiration to most of the great composers who passed through Paris before and during the 20s, and then for many more decades she also taught in England and the US. Milhaud was a student, Stravinsky was her friend (she conducted the premiere of his Dumbarton Oaks). Aaron Copeland adored her and she played the premiere of his Organ Concerto in New York. When I was in high school I somehow ended up in a class she gave for two weeks at the Cleveland Institute of Music. I was way out of my depth in every possible way, but what struck me about her was her imperial style. Nothing that she said sounded as if it had not already been said dozens, if not hundreds of times, as if she were reading from granite tablets.

Imagine this: Nadia Boulanger’s father, a composer, was 70 when she was born. Which meant he was born in 1815, the year Napoleon escaped from Elba and briefly came back to power! Her mother was a Russian princess. Her younger sister, Lilli, born when her father was 74, was a very fine composer, and died at 24, leaving Nadia with a profound case of survivor’s guilt that she would never shake.

What did Boulanger teach her students that, through them, shaped 20th century music? She believed in masterpieces. She didn’t claim to know how they came about, but she encouraged her students to constantly strive to create them. She encouraged them to trust their own voice and helped them become strong, individualistic composers.

Among Gershwin’s goals when he went to Paris in 1925, when the whole world was beginning to hear Rhapsody in Blue, was to deepen his chops as a serious composer. He went to Boulanger, hoping to study with her, as his friends Aaron Copeland and Darius Milhaud already had. But Boulanger turned him down, saying ‘I have nothing to teach you.’ Gershwin often repeated this remark as a compliment, but no one knows for certain whether that was the intention. Having known Boulanger ever so slightly, I would venture she was being dead honest. She could see that Gershwin’s voice, and his potential for masterpieces, was fully formed.