12. Eye Contact

If the only way you listen to music is a streaming service, then you might prefer to skip this chapter, because it’s about some music that mostly makes sense if you’re actually there, in person, to see and hear it. We’re talking about concertos — music written for performing geniuses to show off in the middle of a symphony orchestra concert.

A typical classical orchestra concert, whether summer pops in an outdoor venue, or in a concert hall during the regular season, usually will start with something short and light to let the audience settle down and clear their ears. These little appetizers (your hound will understand the concept if you offer them a crackly pig’s ear) help the audience members let their long-term attention spans take over.

And then, not always but often, comes the middle of the concert sandwich — a person who has flown in for a few days to play just one piece and then disappear on their globe-hopping journey, not to be seen for another year or more. This is the star of the evening. Their piano is in front of the orchestra, even in front of the conductor. If they’re playing a violin or cello, they’re still right at the front of everybody else, but they’re also to the side of the conductor so the two can raise eyebrows at each other from time to time. Try this exercise with your hound a few times and see how well it works to get you in sync.

The concerto is the essence of live music, of the very idea of performance, and until you actually witness what’s going on, no matter how many recordings you might listen to, you won’t be getting the whole meaning of what a concerto is for. It’s actually more than just music — it’s a high-wire act, and no two performances are going to be alike. There’s often electricity in the air, and if the soloist connects with the audience and vice-versa, then ‘events of a lifetime’ can take place.

Prosceniums are the fourth wall of the theatrical experience. We have them in ancient theatres, in movie palaces, and in many traditional theatres. The proscenium says to the audience, We’re up here on stage performing, even murdering each other within our three walls, and you out there can watch from a safe distance because you’re behind that imaginary fourth wall. But the concerto performer, like a stand-up commedienne, breaks through that imaginary wall, peers directly at the eyes of audience members, and declares, “We’re all in this together.” The protection of the fourth wall is momentarily breached. Emotional immediacy may follow.

Without a soloist in front of the orchestra, the orchestra is focused on two things: the music on their stands and (hopefully) the conductor. So the conductor’s back is to us, and the proscenium isn’t breached until the piece is over, when the conductor turns to us and acknowledges our applause, and even the orchestra will stand and bow and look out over the audience, peering into our murky darkness. But concertos are different.

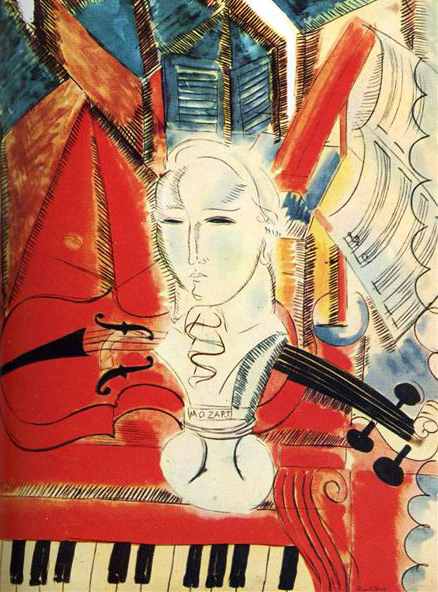

I need something to play!

Imagine being one of the greatest geniuses of any age. You are Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and you’re travelling from court to court showing off your incredible piano and violin abilities. There you are, with the orchestra behind you and, whoa! Someone forgot the concerto!. It wasn’t really that bad, but concertos were scarce, so Mozart began to write his own when he was 11. By the time he was 17 he wrote his first geniuine original piano concerto, and continued to write more until he had written 27, and they comprise an important part of his compositions. Somewhere in the world, right now, a performer sits at a piano in front of an orchestra, and is playing one of Mozart’s concertos. My mother’s favorite Mozart pianist, probably because of how much fun one might have pursing your lips in order to correctly pronounce his name, was Robert Casadesus, (ka-SAD-a-SUE), and when he came to Cleveland to play with George Szell conducting, they established the gold standard for Mozart piano concertos.

This next part may be better understood by your dog than you. I suggest your read this out loud to them and then they’ll try to explain it to you in dog-to-human language:

Concertos are generally made up of three seperate pieces, or movements. The three together make a whole, and that’s why we don’t bark or applaud until the end of the third movement. The first movement generally starts out to discover who is going to be the alpha dog here — the orchestra or the soloist. There’s a fair amoung of sniffing around at first (you know what I’m talking about) and themes and melodies are traded back and forth, each showing off. Eventually they get a little tired of it all and the first movement ends in some kind of agreement about who’s boss. After that exciting first round comes the second movement, in which the soloist attempts to demonstrate the meaning of limpid to the audience. Now, you already know what it means — it’s like lying on your favorite bed, in the sun, chewing lazily on your favorite bone, which is never going to be completely done. So that’s the second movement.

The third movement is even more of a show-off than the alpha dog movement, with the orchestra and the soloist competing to show who can play faster and more complicated stuff than the other. This is like Westminster and a doggie Olympics all rolled into one. Please use your indoor voice and explain all that to your human partner!

Okay, you can tune in again, Human Partner.

Now you know what a concerto is and why they came to be. Next you need to take a crash course on most important concertos, so you can check them off your bucket list, and appear to be insanely knowledgeable about all things concerto. These following numbers are really, really important numbers to know, because you do not ever in your life want to humiliate yourself by casually mentioning how much you love the Second Brahms Violin Concerto. He didn’t write it and you don’t love it.

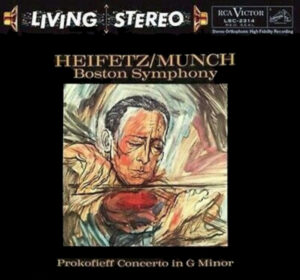

The great violin concertos you’re likely to encounter any given summer: Mozart wrote 5, Beethoven 1, Brahms 1, Tchaikovsky 1, Sibelius 1, Bruch 2, Lalo, 1 (called Symphonie Español), Stravinsky 1 and Prokofiev 2. Yes, I left a lot out, but believe me, this is the core. (I’m expecting some incoming cavilling that I forgot Mendelsohn. No. I did not.)

Piano Concertos: Mozart wrote 27, Beethoven 5, Brahms 2, Tchaikovsky 3, Ravel 1, Poulenc 1, Rachmaninoff 4, Prokofiev 6, Stravinsky 1 (not for an entire orchestra, but for wind instruments, and don’t miss it.). And George Gershwin wrote a beaut, and it’s not called Rhapsody in Blue.

Cello concertos: Dvorak 1, Elgar 1. That’s it? Yes, slim pickings and/or bowings for cellists. Okay, Haydn wrote one also, but it’s pretty much for students.

Concertos for more than 1 soloist and orchestra (these are really wonderful and rare because they’re expensive to perform, so if you get a chance, go!!) Mozart Sinfonia Concertante for Violin and Viola is one friend’s all-time favorite Mozart piece. Beethoven’s Triple Concerto for Violin, Cello and Piano is fun, and Brahm’s Double Concerto for Violin and Cello is always on my desert island list.

You will also find concertos for every other possible instrument, from kazoo to tuba and beautiful ones for French Horn and organ. But these are rarely heard live because, in the rarified world of touring soloists, there are lots of pianists and violinists, a few cellists, a clarinetist or flutist once in a while, but you get the picture. No huge supply of concert piccoloists, nor much of an audience for them, and hence few piccolo concerto performances.

Next warm summer day — pack a picnic, find a concert tent or lawn, bring some crackly pigs’ ears (no, not for you) and settle in for a concert: appetizer up front, a concerto and soloist to provide the meat in the middle, and, after intermission, a proper symphony.

Now that you’ve gotten off the couch and gone to some live performances, you might want to listen to recordings of some of these concertos with your four-footed friend and, if you have them, your kids. I’m going to make a few suggestions, even though there are dozens of great fiddlers and pianists on recordings. But there are also some performers who are so wonderful that you simply need to know them. For violinists, in the past century, for almost the entire century, Jascha Heifitz was the standard for perfection. Incredible technique and a range of tonal color that will delight you. The more influential violinist, meaning the one who is cited as the greatest inspiration for other violinists, including all who are playing today, is David Oistrakh. Without having already listened to him, what I’m about to say won’t make a lot of sense. But when you have listened, it will. Oistrakh brings a sense of humanity to everything he plays. He can make you proud of simply being a human being. For those currently performing, don’t miss Lisa Batiashvili playing the Sibelius Violin Concerto. Same for Hilary Hahn.

For piano concertos, I find myself returning to Wilhelm Kempff for the five Beethoven concertos. He’s simply elegant — you forget that someone is playing these. He’s just transparent to the music. For the Brahms First Piano Concerto, try Rado Lupu, whose recording is terrifying. For Rachmaninoff’s three piano concertos, at some point listen to Rachmaninoff’s own recordings. They’re salvaged from 78s, but it’s stunning to hear the ur-text. For more modern recordings, Vladimir Ashkenazy has the chops to bring them alive.

And for Gershwin’s wonderful, tuneful and jazzy piano concerto, don’t miss Earl Wild, who heard Gershwin perform his concerto and is faithful to the composer’s intent.

A kinescope is how live television shows were once recorded. Basically, a 16mm. camera was set up in front of a television monitor. The grainy results are pretty wretched, but in some instances, that’s all we have. Which brings us to the Elgar Cello Concerto. I really don’t want to make you (or Mr. Bad Breath over there) cry, but I need to introduce you (if you haven’t already found her) to Jacqueline du Pré, the cellist. She developed multiple sclerosis and stopped performing at 28. She and the Elgar Cello Concerto are indivisible, and you can see why when you find a kinescope of a broadcast of her performing it (YouTube.) There is a much better film about her released by Allegro Films in 1989. For audio recordings of the Elgar Concerto, I’ll think you’ll enjoy, throughout your life, the one du Pré made at 20 with Sir John Barbirolli conducting the London Symphony Orchestra.