5. Ants in Your Pants

Nothing is worse (well, that’s a bit of an exaggeration but I’m trying to make a point) than being forced to do the exact opposite of what you’re currently doing. If comfortably curled up on the couch with some great music on and someone near you decides they need to go out right now, that’s worth a groan.

And then there’s ants, or as I used to hear as a kid, shpilkes, as in, “Geez Gerald, can’t you sit still even for a moment? You must have shpilkes.” It was a number of years before I discovered that shpilkes was Yiddish for ants. Ants in your pants.

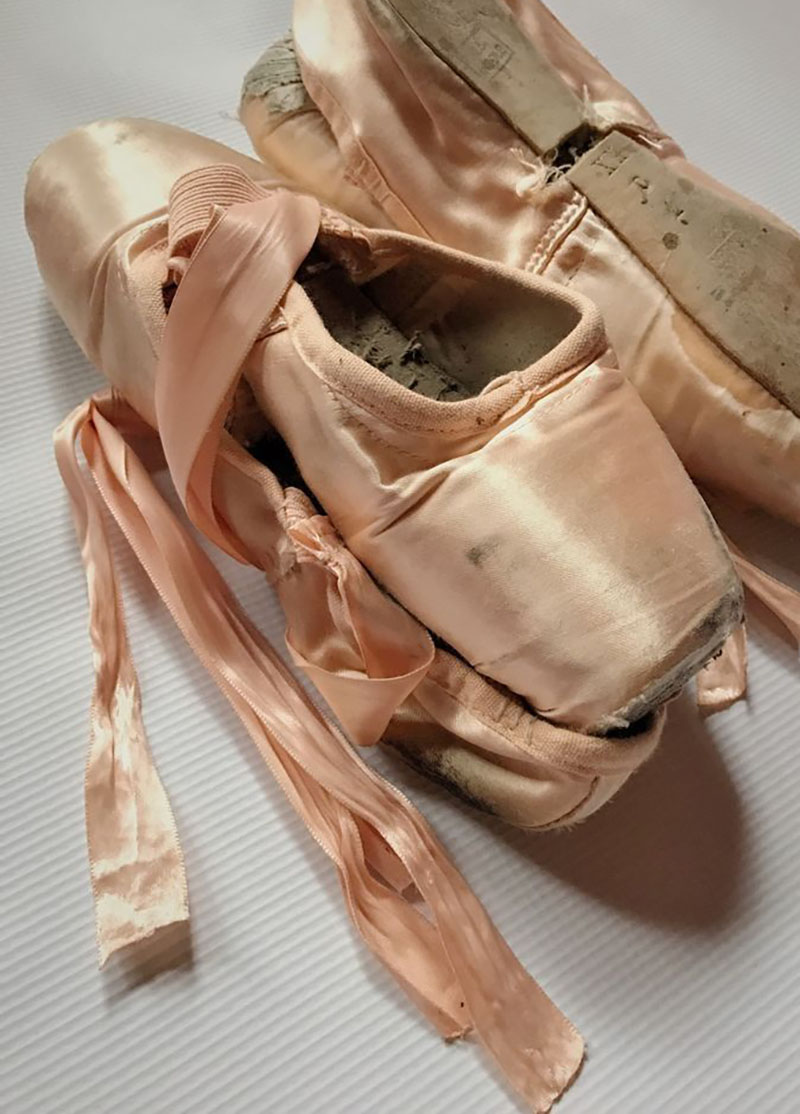

Which brings us to sitting still for classical music. Some music we’ve been listening to already may have been a little shpilkes-inducing for you or some two or four-footed friend trying to share your discoveries. So let’s move on to music that’s meant to be moved to. If a lot of music began in the stillness of cathedrals, a whole other music in the secular world was meant to be danced to, and marched to. This is music with strong, regular beats, usually grouped in fours. The first of the four beats usually has a little more emphasis on it, so that players and dancers are usually pretty sure where they are in the count.

ONE, two, three, four. ONE, two, three, four. But take care! March to that for long enough and you might feel like invading a small country.

Folk and country dances have often been adopted by classical composers. Two sets of these, one by our friend Johannes Brahms and the other by Antonin Dvořák (pronunciation break: devore and Jacques with a soft ‘g’) are often on albums and concerts together, since they share the same kind of energy and feel of a village getting together for a night of dancing. Try to find the recording of the Brahms Hungarian Dances made by Iván Fischer conducting the Budapest Festival Orchestra. Fischer did a lot of research to bring a fresh view of this music and I think you’ll find it really exciting. For recordings of the Dvořák Slavonic Dances, you can take your pick, but just like local wines seeming to fit so perfectly with local cuisine, Eastern European orchestras are going to be more authentic (and therefore freer) with their own music. Find András Keller with the Budapest Symphony Orchestra. If you get stuck with a recording that’s a little heavy or draggy, you’re probably spooning the wrong goulash. Don’t hesitate to try other performances until you find one that grabs you.

Performance in classical music is really a big deal. In popular music, songs are developed layer by layer in the studio until the artist is happy with the final result, and that’s the recording that becomes the standard version of the song all over the world. Sure, somebody might cover it and change it someday, but the original will always be the original. Classical music is, with some exceptions of course because there are always exceptions, totally different. Nobody knows how a great many composers who died decades or centuries ago really wanted their music to sound. Even when we have a composer’s own recording, believe it or not, that might not always be the best performance of the piece. You might wonder how could that be? Igor Stravinsky, one of the great composers of the 20th century recorded most of his work, but there are lots of performances much better than his. Why? Because he wasn’t the greatest conductor of his work.

Composers are strange animals. You’ve probably heard that Beethoven was deaf for much of his mature life and you probably wonder how in the world he could have composed so much amazing music. If you’ve known many composers, this might not be amazing at all. I have seen composers who read music on the printed page — and these are huge sheets of music with separate parts for dozens of instruments all playing something different at the same time — and they can hear the whole complex thing as if it were being played right then!

Franz Schubert, who wrote really beautiful music but died young and wasn’t recognized as great until long after he died, wrote symphony after symphony which he never heard except in his head. The American composer Charles Ives, who spent most of his life selling insurance, only heard one of his several symphonies performed — and that was on the radio!

What happens when a composer like Stravinsky, who already hears his compositions in his head the way he wants them, gets up in front of an orchestra to make a recording? The musicians are excited to be conducted by the genius himself, the composer waves his arms around so everyone goes at the right speed, and the recording is made. But something can easily go wrong — I can’t even hear that important bassoon part! And what about the balance between the strings and the winds? What happened to the violas?

And the answer is — the composer heard them all in his head whether the balance in the orchestra was perfect or not. So generally, if we’re looking for the greatest performance of something, often the composer should have let someone else take the baton.

And this gets us close to what performers should be doing when they bring us music. They are meant to be advocates of the music, trying to make clear what’s in the music so beautiful or interesting or powerful enough for each of us in the audience to be able to get it, to see the beauty that the performer found in the music in the first place.

And that’s why, throughout these posts, I’ll often be suggesting which performance you really ought to try to hear. If I mention some really terrific piece and Spotify or some other streaming service offers you a boring performance, you’re not really hearing the piece because the performance is in the way, like someone standing between you and the Mona Lisa.

Gioachino Rossini is a composer from the early part of the 1800s who could knock out one gorgeous opera after the other, some created in as little as a few weeks. One of the unusual mysteries about Rossini is that at the top of his fame and career, he suddenly quit. He declared he had made enough money and that was it. It was a little like Shakespeare retiring in his mid-forties to go home to Stratford and farm. One of the most delightful pieces of music for dance is La Boutique Fantasque which was put together in the early part of the 20th century by a second composer, Respighi, based on various piano piece by Rossini. The piano pieces are rarely played, but the ballet has been a favorite around the world for more than a century.

Normally I would suggest going to Spotify and find La Boutique Fantasque and then grab your chihuahua and start leaping around the room, but it’s trickier than that. Spotify will offer you seven versions of La Boutique, okay so far. But if you pick one of my favorites, conducted by Arthur Fiedler with the Boston Pops — Whoops! Spotify doesn’t start at the beginning. It’s like dropping the needle halfway through. Grrr. Then you might try another favorite of mine, the conductor Frederick Fennell (true confession, I played and barked as a dog in a piece he conducted) but the recording that Spotify is going to play isn’t actually La Boutique Fantasque at all! It’s another piece on the same record.

What the heck? How are you going to start enjoying classical music with your dog if you can’t even find the music? You can try Amazon, where their streaming service at least shows the 8 parts of the ballet in the right order, so you know you’re starting in the right place and getting all the way through to dessert.

Best streaming if you want to keep exploring classical with or without me might be Idagio. Idagio is devoted to classical music, so they don’t dumb everything down to be treated as a ‘song’ and they label most everything correctly. If you search for La Boutique Fantasque you’ll find a good selection of great performances. While I write this I’m listening to Vasily Petrenko conducting the Liverpool Orchestra and it’s quite a blast.

I did mention march at the beginning of this post and I’ll bet Mr. Shpilkes over there is getting a little bored watching you ballet all over the room, so here’s a thrilling Suite for Band #1 by the British composer Gustav Holst which is made of three short-attention-span sections, ending with a March that is famous (when Frederick Fennell is conducting) for taking out a lot of woofers (of the paper kind, not those often found at the end of a leash, thank goodness.)